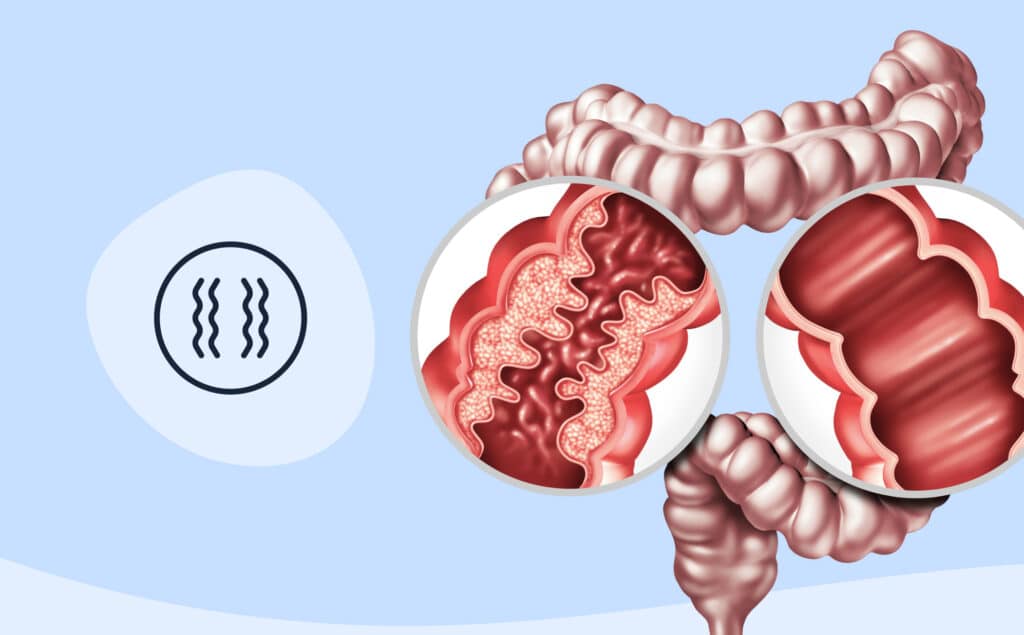

If you’re living with IBD, chances are you’re pretty familiar with your bowel movements. But how much do you really know about stool and how your body passes it?

First of all, what is poop?

Producing stool is the digestive tract’s way of getting rid of waste. Poop is made up of the solid and semisolid food that could not be digested in your small intestine. In addition, stool contains waste products made by bacteria that normally live in your intestines and unneeded substances or cells produced by your body. For example, bilirubin (a breakdown product of red blood cells which gives poop its brownish hue), degraded waste products in the bloodstream, and dead cells that normally slough off from the lining of the gut are all found in stool.

What goes in must come out

When it comes to poop, there really is no “normal.” Everyone’s system is different. However, we can say that it typically takes about 6 to 8 hours for the food you’ve eaten to pass through your stomach and small intestine. Then it moves to the large intestine for further processing. As for when your food will come out the other end, that varies.

How often people poop also varies considerably—even without factoring IBD into the equation. Healthy individuals may pass stool anywhere from several times in a single day to once every couple of days. It’s considered constipation if this process is delayed for several days.

A rating scale for poop

Believe it or not, there is actually a rating scale for poop. It’s called the Bristol Stool Scale, and it includes seven poop categories. (These folks do use the word normal, but try not to let that throw you off!)

The seven categories are:

- Type 1 (constipation): Separate hard lumps that are hard to pass

- Type 2 (mild constipation): Lumpy and sausage-shaped

- Type 3 (normal): Like a sausage, but with a cracked surface

- Type 4 (normal): Smooth and soft, like a sausage or snake

- Type 5 (lacking fiber): Soft blobs with clear cut edges that are easy to pass

- Type 6 (mild diarrhea): Mushy, fluffy, with ragged edges

- Type 7 (diarrhea): Watery or entirely liquid

Again, while we hesitate to say that anything is “normal” when it comes to poop (and lots of other things, come to think of it), the Bristol Stool Scale can give you some indication of what’s going on with your digestive system. Also, it’s a really handy tool for describing your poop to healthcare professionals.

The poop rainbow

Typically (there’s that word again!), stool is semi-soft and brown with a mucus coating. However, stool naturally changes color at different times, so seeing something other than brown in the toilet doesn’t have to be cause for alarm.

Here are some common shades of poop, along with what may be causing them:

- Green poop: If stool is moving through your large intestine too fast, a deficiency of bile could be what’s causing that green color. However, the green hue also could be caused by ingesting leafy greens, green food coloring, or iron supplements.

- Light, white, or clay-colored poop: This could indicate a lack of bile in your stool, which could be caused by a bile duct obstruction. However, certain medications, like anti-diarrheal drugs, also could be the cause.

- Yellow, greasy, and foul-smelling poop: This could be caused by gluten, or it may indicate too much fat in your stool, possibly due to a malabsorption disorder like celiac disease.

- Black poop: Bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract can turn your stool black, but before you panic: so can black licorice, iron supplements, and bismuth subsalicylate (Kaopectate, Pepto-Bismol).

- Red poop: Foods like beets, cranberries, tomato juice or soup, and red food coloring can give your poop a reddish hue, but so can bleeding in the lower intestinal tract (large intestine and rectum).

When should you call a doctor?

If your stool is black or bright red and you have not ingested anything that’s an obvious cause (like lots of red beets), seek medical attention immediately. Additionally, it’s important to take note of your patterns, like how frequently you typically go, and contact your doctor if you notice changes to that pattern.

Medically reviewed by Jonathan Hansen, MD, Ph.D.

Oshi is your partner in digestive health

Feel like your digestive concerns are running your life? You’re not alone—and we’re here to help you find lasting relief.

Oshi Health GI providers, gut-brain specialists, and registered dietitians work together to address the root cause of your symptoms and find solutions that actually work for you.

Whether you’re dealing with chronic digestive issues or unpredictable symptom flare-ups, our GI specialists deliver:

✔ Personalized care plans tailored to your lifestyle

✔ Science-backed strategies to calm your gut

✔ Compassionate, whole-person care

✔ And so much more!

Ready to take control of your gut health?